It’s a long-acknowledged fact among video gamers that sometimes, a game just gets changed for reasons unknown when it gets imported to another country. There are the obvious changes (Japanese games imported to America tend to have sexual content toned down; German versions of first-person shooters tend to have violence heavily censored), but then there’s those really bizarre changes that nobody can really explain, like all those Sega Master System games that randomly became mascot vehicles for a popular Brazilian cartoon character. One category of those changes that is strangely under-reported: Japanese versions of Western games that are given a radical overhaul. And the subject this time is Super Solitaire, developed by Australian company Beam Software and released for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System in 1994. Before we go into what changed, let’s look at the game as it was intended.

Super Solitaire was most likely developed to get quick revenue for Beam’s other projects at the time. Or perhaps publisher Extreme Entertainment Group decided the Super Nintendo didn’t have enough card games (notwithstanding the likes of Vegas Stakes and Super Caesar’s Palace, anyway). Either way, what we got was a reasonably competent collection of 12 solitaire games, from classic Klondike and Freecell, to the slightly more obscure Scorpion, Aces Up, and Florentine Patience.

By default, the game is controlled with the standard SNES controller, piloting a mouse cursor around the screen (the speed of which can be changed in an options menu, but not during the game). It’s awkward at best, but at least seems more consistent than how Game Boy Color games tended to handle it. Alternatively, owners of a Super Nintendo Mouse (i.e. people who bought Mario Paint) could use that instead, and play Solitaire as she was intended, albeit retaining the point-to-point interface instead of having card dragging. (It’s not like the SNES would have had problems rendering that, anyway.) The game keeps running statistics, but the cartridge did not ship with battery backup, so you are required to retrieve a password to save them.

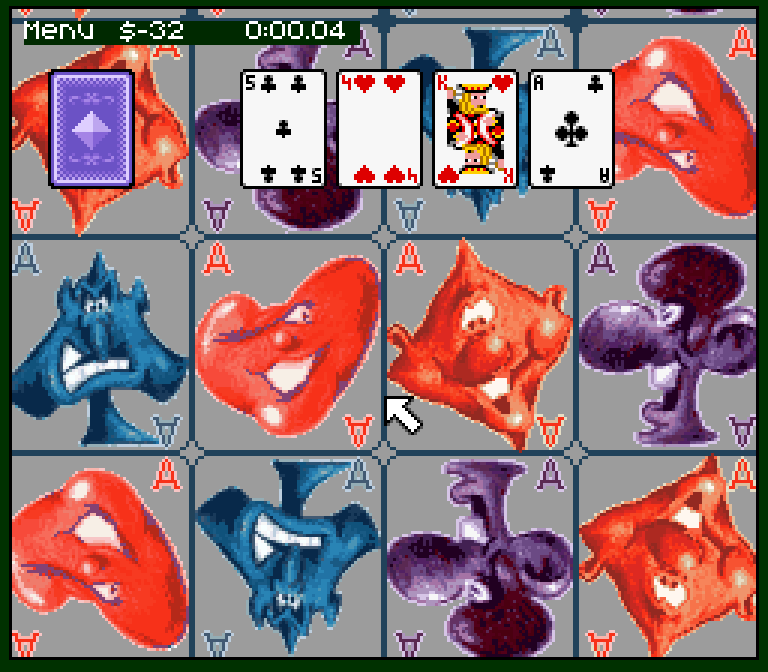

When Super Solitaire was considered for localization to Japan, publisher Pack-In Video decided that they didn’t want just a quick-and-easy translation (not that there was much text in the game to begin with, outside of the menus). Instead, they hired Gainax illustrator Takami Akai, notable for the character designs in the Princess Maker series, to redraw all of the backgrounds, the win/lose screens, and…basically 75% of the game. The resulting game was released for Super Famicom as Trump Island in mid-1995.

And while the music and sound effects are completely unchanged (even retaining the original game’s option to have the cards make burp and fart noises when moving), the entire menu system and presentation of Trump Island is equal parts more interesting and less easy to explain. See, Takami Akai is a character designer, so instead of having the background images be regular old backgrounds, he added a character to each game. And the results are…well, arguably fetishy, with swimsuits, gothic vampires, princesses, and a mean-looking lady with a whip.

Trump Island retains all the same features, including the password system. Why would one decide to play one over the other? Well, fans of Takami Akai’s character designs would find much to celebrate in the Japanese release, but the menu system is a bit confusing if you’re not able to read the text. It’s certainly possible to fumble your way through it, with some familiarity with the English release. But then there’s the overworld map that serves as the game select menu:

The world map bears several landmarks that all link to one of the 12 solitaire games. Some are fairly obvious; Pyramid is shown here as a pyramid, there is a small golf course that starts a game of Golf, and the police car begins Freecell. But in what world would Klondike be related to a castle? What does a beach chair and umbrella have to do with Aces Up? Just what game does the space shuttle start? Why are there dolphins? My head hurts.

Ultimately, though, in a world where you can find solitaire games nearly anywhere (and with better controls, to boot), the best reason to be interested in this game is if you’re either a fan of Takami Akai, if you’re interested in the weirdness factor of owning a solitaire game for a system not known for having solitaire on it at all, or if you really just want to play a card game where the cards can be made to sound like burps, cows, or tanks. If not for those things, there’s not much remarkable about it, even among solitaire games. The story, I suppose, is more interesting than the game itself.

My own comparisons between Super Solitaire and Trump Island are by no means exhaustive, of course; if you want a full rundown of all known differences, The Cutting Room Floor has a much more comprehensive list.